Power to the Wearables

Wearable tech comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes, ranging from 3D printed shoes that promise to match your feet exactly to bracelets that make you feel hot or cold (regardless of what the actual room or body temp is) to a watch that’s a simple phone and includes a GPS tracker–intended to track your kids.

Wearable tech comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes, ranging from 3D printed shoes that promise to match your feet exactly to bracelets that make you feel hot or cold (regardless of what the actual room or body temp is) to a watch that’s a simple phone and includes a GPS tracker–intended to track your kids.

Power to the Wearables

An intriguing trend within wearable tech has been power-generating garments. One example has been the SolePower, a shoe that takes the kinetic energy made by walking around and converts it into electric power, then stores it in a battery pack that can charge a phone. Other wearable power plants include jackets with solar panels in the back and–perhaps most interesting–a new fabric that uses static electricity as the power source.

Static Electricity – The Next Way to Power Your Device?

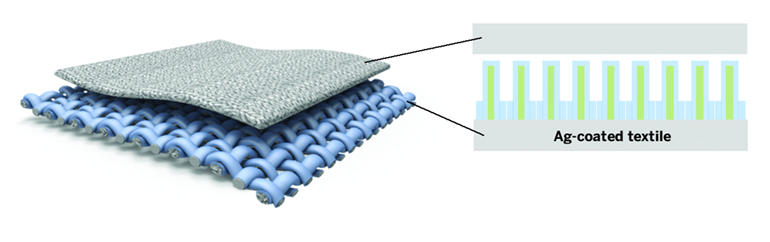

The new fabric (called a wearable triboelectric nanogenerator, or WTNG) was created at South Korea’s Sungkyunkwan University by a group of scientists led by Sang-Woo Kim. It’s made of two layers of fabric: one of silver-coated fibers, the other made of zinc oxide nanorods coated with polydimethylsiloxane (a silicone used in many consumer products–try pronouncing it!) When the wearer moves in typical day-to-day motions, the two layers rub together, producing a triboelectric effect–the same thing that causes the static electricity made when, say, when a balloon is rubbed on hair or silk on glass. When the two materials rub together, electrons transfer between the surfaces, which creates a positive charge on one side and a negative charge on the other.

When the materials separate during the motion, this creates a small electric current–something akin to the “snap” you get when you reach for a metal doorknob after walking on the carpet on a windy day. Thankfully, not every pair of materials does this, or walking down the street would be a little more, ahem, electrifying than it is. Professor Kim and his team found that silver and nanopatterned polydimethylsiloxane were the best matches. The 100-nanometer zinc oxide nanorods increase the contact area, which equals greater friction and therefore greater power output. Also, the more layers there are, the greater the output.

Attached to a jacket sleeve, the fabric successfully powered six embedded LEDs, a small LCD, and a keyless car remote inside the jacket. The wearer’s wrist movements produced enough power–without any external power–to turn each device on, although only one at a time.

It has its limitations. It couldn’t, as it is, power a smartphone, although perhaps if paired with a battery pack, it could store the power generated for emergencies. And don’t expect whole jackets of this material just yet–a silicone jacket would get sweaty fast.

So the question is, will we see wearable tech move into the decorated apparel market? It probably won’t get as popular as the famous Hanes Beefy T, but wearables might very well move into the space if popularity increases.

Anyhow, now it’s back to the shop and managing those orders.